Henry Lansing Woodward

© Copyright 2023 by Henry Lansing Woodward

Photo courtesy of the author.

|

The Reno Syndrome Henry Lansing Woodward © Copyright 2023 by Henry Lansing Woodward  |

Photo courtesy of the author. |

Then

I hit our

unconscious patient in the middle of his chest on the breastbone

with the side of my closed fist, and he

awoke immediately. His heart was

beating again with a regular rhythm but beating too fast.

After leaving the ER from our previous call, I radioed dispatch and again asked permission to drive to our respective houses to change our uniforms and have lunch. The time for breakfast had long passed.

“Yes, go ahead,” they answered, but they called again in less than five minutes. It was for another “man down.”

This nebulous term is used a lot by dispatch services. Others similar to it are “fall case,” “domestic,” “MVA,” “difficulty breathing,” and “possible choking,” and none of them tell us what we need to know.

Perhaps it’s a throwback to the fifties or sixties when ambulances were little more than taxis with red lights, sirens and maybe some oxygen. In those days, the attendants were “ambulance drivers,” not trained medical caregivers, especially not RNs or Advanced Life Support Technicians - Paramedics. The dispatchers were the same with no medical training, so instead of saying, “Intracranial Bleed,” it was a “fall case,” and so it remains today.

Change comes hard. Change scares people. Our next patient was experiencing an unanticipated change in his health, and he was in full denial.

This case was at the Nugget Casino in the City of Sparks, Nevada, “across the street from Reno,” as the town is known.

We were informed the man had collapsed (The first time.) inside the north parking lot entrance. After responding with lights and sirens, we found a casino official waiting inside the door. The man and his wife were standing beside him in the middle of the carpeted hallway.

The man had just told the security officer he didn’t need the ambulance and was trying to leave. He had gotten as far as the door where the official and the man’s wife tried to talk him out of it. We arrived just in time.

As my partner and I entered the hallway, the man started to walk toward us. Before anyone could speak, he passed out cold turkey and hit the floor. (The second time.) This was not a good thing for a man who looked to be in his sixties or so.

Reno and Sparks are at an elevation of more than four thousand feet above sea level. Because of this, the air has less oxygen in it, which can be a problem for many visitors, and it was. In reality, it was a problem for so many visitors, it even had a name. We called it The Reno Syndrome. Maybe they still do.

Most people who come to Reno do so by airplane, meaning they must walk more than they ever did at home. All that extra walking, eating, and drinking at over four thousand feet can take a toll. This is especially true if a person is an older male, carrying a little extra weight, and has underlying health issues.

With this man unconscious on the floor, I immediately felt for a pulse. I found he had a good one, strong and regular. At the same time, I was thinking about this syndrome and how he didn’t fit the picture.

This man was thin and looked healthy. As we put him on oxygen and applied the heart monitor, his wife told us he didn’t smoke or drink. She also said he had no medical problems, took no medicines, and ran marathons. Something was very wrong with this picture. Before I could apply the monitor and put on the oxygen, he awoke.

“I’m fine,” he said as he pulled himself into a sitting position. “I don’t need all this stuff, and I don’t need the ambulance or the hospital. All I need is a little rest.”

No matter what I said, he just wouldn’t go with us. He was adamant. I checked his pulse again and found it was regular and of normal speed, so I couldn’t say much. I did tell him there might be a problem happening that was not yet visible, but he would not listen.

Then, as he stood before me, he said, “I don’t need…” and passed out again and hit the floor (The third time.) I again checked for a pulse and could not find one at the wrist or in his neck. There was no pulse. His heart was not beating, and I didn’t think he was breathing.

Just as my partner was about to start CPR and I was about to put a tube into his windpipe so I could breathe for him, he awoke once again. I felt his pulse, which was regular but a little too fast. He had been out longer, and his heart and breathing had stopped. This time, he was confused, probably due to his brain's momentary lack of oxygen. Still, he would not go with us.

I knew this man needed to be in a controlled medical environment, so I would not give up. “You must see a doctor,” I told him. “Something is going on with you, and if you were my brother, father or uncle, I would insist you go now. You must come with us. If not for yourself, do it for your wife.” Finally, with his wife insisting, he agreed.

We put him on the gurney and moved him into the ambulance. My partner started driving as I inserted an IV and put him on oxygen. I also attached the heart monitor so I could see his heart activity.

His wife was in the patient compartment riding with her husband, and my partner was driving in normal traffic. Then he passed out again. (The fourth time.) Now things were serious. I looked at the monitor, and there was nothing. Flatline. No heart activity at all.

“Let’s go! No heartbeat!” I yelled to my partner.

I heard the sirens kick on and felt the ambulance lurch forward as we changed our driving to lights and sirens. Then I hit our unconscious patient in the middle of his chest on the breastbone with the side of my closed fist, and he awoke immediately. His heart was beating again with a regular rhythm but beating too fast.

What I had done is called a “Precordial Thump.” The impact of the blow can generate a low electrical shock within the heart tissue, stimulating it to beat again. When I used it on this man, it was the first time I had ever done it, and it worked.

“The thump worked! His heart is beating again,” I yelled to my partner over the noise of the sirens. As I did, his heart stopped, and he passed out again. (The fifth time.) I thumped his chest one more time, and immediately, he awoke. I continued applying soft thumps to his chest with the frequency of a beating heart in a technique called “fist pacing.” As long as I continued doing this, he remained awake and talking but was now completely disoriented.

I thought that if he was talking, even though his words were nonsensical, he was breathing on his own, and this was a good thing. I was still thumping when we pulled into the ER with the sirens still running.

I had told my partner to keep the sirens on as we pulled into the ER parking lot, and we were never supposed to do that. It just wasn’t done. All sirens were to be turned off before arrival so they did not bother the patients in the hospital.

Because it was a short and fast transport, dispatch did not have time to notify the hospital we were arriving with a critical patient. It was up to us to alert them. Thus, the sirens. Even though I knew it would only be about a four-block notice, I thought that would be better than nothing. At least it would give them time to put down their coffee cups.

We were still parking when a nurse stuck her head out the ER doors, and there was anger on her face. Before she could say a word, I yelled, “Pacemaker!” That was all I had to say. Immediately she turned and disappeared into the ER.

My partner pulled the gurney with our patient on it from the ambulance and then began to push it toward the ER doors. I stepped onto it and stood on a lower railing near the ground that runs along the side, front to back. Doing this allowed me to continue fist-pacing without running alongside the gurney. The external pacemaker was ready and waiting before our patient was on the ER bed.

An external pacemaker is a device attached to the skin in the area over the heart and does the same job as fist pacing. It uses a low voltage electrical charge to stimulate the heart to beat and does it in a controlled manner. It is adjustable in voltage intensity and frequency of discharge.

While this device supported the patient, the doctor inserted a catheter pacemaker through the big vein in his neck and into his heart. After he completed the procedure and it was working, the nurse removed the external pacemaker. Finally, the patient’s heartbeat was managed, and he had a chance to survive.

Then the doctor turned to me and asked, “What’s that smell?”

Once again, I explained the situation. The doctor offered to lend us some ER green “scrubs” worn by the staff in the OR and the ER. We accepted his offer.

At last, after about four hours, we were out of our smelly clothing.

This

man may or may not have been a victim of The Reno Syndrome, but he

did have a full-blown heart attack in the part of his heart that

regulated its beating. The reduced oxygen content at over four

thousand feet above sea level may have been the trigger, or perhaps

it was just his time. Whatever the cause, that day in Reno, the

precordial thump and fist pacing saved this reluctant man’s

life.

A

few days later, my partner and I visited our patient in intensive

care. He didn’t remember the ambulance ride or anything about

the whole event. He didn’t even remember the carpeted hallway

inside the casino’s door. His wife did, though, and was very

gracious in her thanks.

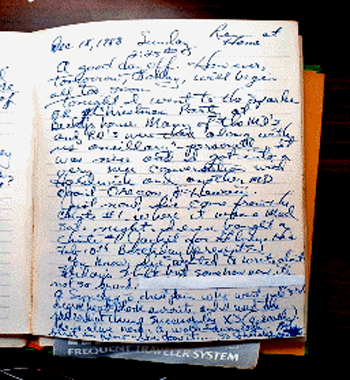

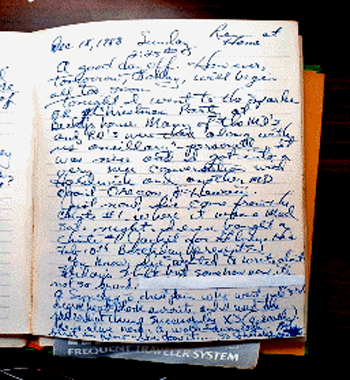

I’ve attached a copy of my diary entry about the case. It was written three days after the event and is an abbreviated entry, almost just a footnote for such a significant call. Below is the transcribed entry. I’ve written it here so it is easier to read.

“You know, I’ve wanted to write about Friday’s shift, but somehow now it’s not so grand. A Syncope (not Syncope, it was fainting, my note.) without chest pain who went into (“a,” My note.) 3rd-degree heart block (Actually, he had a cardiac arrest five times, not a heart block. My note.) en route and I used the precordial thump successfully x3 (5 really, My note.). He is alive now. A walk-away code. My first in Reno - I’ve done it. . . So what else is new?”This was a true “save.” The patient lived to leave the hospital with his wife and go home, where he probably didn’t run too many more marathons. We were still cleaning the ambulance when dispatch alerted us again.

So far, we haven’t eaten anything all day or had the time to pee.