Safranesia's Pants

Helene Munson

©

Copyright 2019 by Helene Munson

|

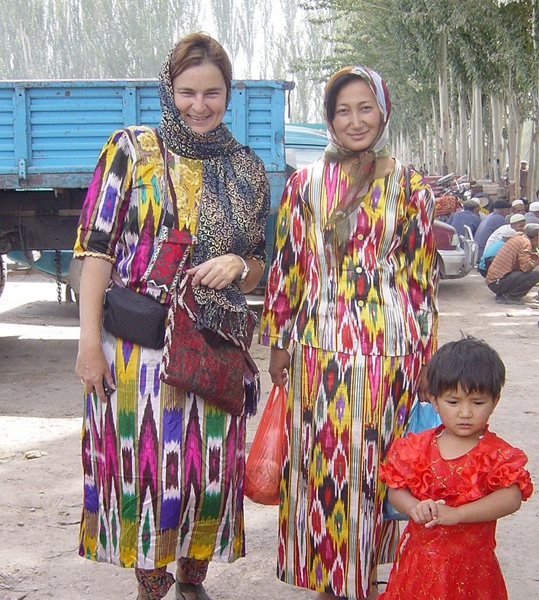

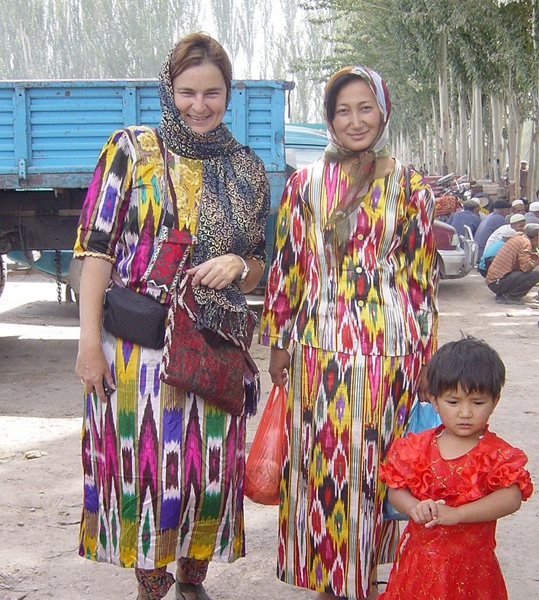

Photo

taken in West China in 2001 while comparing my Turkmenistan dress

and Kirghiz pants outfit to a local woman’s traditional Uighur dress.

My dusty attire shows that this was truly an overland trip, taking

local transport all the way. This area is now off limits to tourists

due to the Chinese crackdown on the local Uighurs' protests

against destroying their cultural heritage sites and replacing them

with Han Chinese architecture. |

My

journey had already been hundreds of miles overland. I was excitingly

close to completing this once-in-a-lifetime trip. But here in front

of the train station in Urumqi it all seemed to unravel. I felt that

I was treated like a rabid dog.

My

thoughts wandered back to earlier parts of my travels. In Samarkand,

I had been invited to a bridal shower. While passing the open gates

of one of the traditional, walled courtyards, I had peeked inside. Food

was being served on rows of tables. A small band played

traditional music as a dancing girl in a rhinestones-embroidered,

lime green dress twirled her long, wide skirt. Seeing the delight on

my face, a man had motioned for me to come in. I joined in the

dancing, but felt ridiculous in my Western attire of cargo pants and

a long sleeved t-shirt.

The

next morning, my first project had been to go to the market and buy a

traditionally striped, silk dress usually worn with a pair of

full-length bloomers. As the dress was three quarters long, I felt

sufficiently covered and decided to forgo the hideously wide pants.

It was a decision I was to regret later.

My

last stop on the Uzbek side had been the sleepy town of Margilan,

with a decrepit Russian hotel. There was not a drop of water in any

bathroom pipe, including the toilet. The next day, unwashed and

uncomfortable, I headed to the market to get a shared taxi ride to

Kirghizstan .

A

woman wanting to be helpful, dressed in jeans and a fashionable top

approached and asked in English: “Are you lost?”

I

responded: “I’m hoping to get a taxi to Osh, so I can

then make it over the Irkesthame Pass into China. I’m on my

way to Kashgar.”

The

woman smiled. “That’s not as easy as you think. It’s

the most direct route, but the Kirgiz Osh truck drivers cross the

border in convoys…they’re afraid of getting robbed. But

my sister, here, can help you.”

With

that she introduced Safranesia, a woman dressed in traditional attire

with her hair covered by a full veil, not just a loose headscarf. The

sisters grew up together. But while Amina, the English speaker

had moved into the capital, Tashkent, Uzbekistan Safranesia had

married a devout Muslim and moved to Osh in Kirghizstan. Once a month

the two women would meet in Margilan to chat and shop.

I

shared a taxi and put on a headscarf to blend in. When we reached

Osh, Safranesia took me to her house, where three children and her

husband greeted us excitedly. She shooed the two boys and her husband

out into the street, and boiled a bucket of hot water on the wood

stove for me to wash.

I

undressed in the yard, soaped myself, and washed my hair in the

half-emptied bucket, keeping some water to wash my underwear. Never

in my life had so little water felt so good.

The

following two days Safranesia took me to the house of the truck

drivers’ head honcho, but there was no convoy that I could

join. The rest of the time was spent visiting women neighbors and,

as rumors of a westerner staying with Safranesia had made the rounds,

they all wanted to meet this strange being. I was served food and

tea. One girl insisted on beautifying me Kirgiz style by drawing a

uni-brow on me with her kohl pencil.

Safranesia

and I communicated in gestures and signs and drew little pictures on

pieces of paper. I had already learned to pretend to be still

married, when talking to curious taxi drivers to avoid obnoxious

offers to become a second wife.

But

while staying with Safranesia I became aware of the irony of how safe

it was for a single woman to travel alone in the Muslim world. I was

kept safe in people’s homes, playing with the children or

helping the women cook. Had I been male, no self-respecting local

man would have allowed a stranger to see his wife and daughters

unveiled in his home.

On

the third day in Osh I realized that I had to find another way to get

to Kashgar in time for the famous, ancient Saturday market. The

night before I left, Safranesia brought a pair of her own bloomers. As

I dressed the next morning, she appeared glad to be sending me on

my way looking more decent with my lower calves and ankles covered.

With my modesty restored, we went to the market square, where

Safranesia negotiated a ride in a shared taxi to Bishkek. The goodbye

was an emotional embrace and she gave me her own Muslim prayer beads,

a well-worn strand made from white glass, which I cherish as talisman

to this day.

Arriving

in the Kirghiz capital, Bishkek, I realized that I no longer had the

time to make an overland crossing via the army-guarded safe Torugart

Pass. I took a flight to Urumqi in western China.

At

the train station, I found that I had missed the day’s last and

only train by half an hour. It meant that now the only way to get to

Kashgar in time was to take a 24 hours bus ride. It also meant that

I had to get a taxi to the bus station in a hurry.

“Tenty

dolla, tenty dolla” the taxi drivers shouted as they encircled

me, grimacing mockingly. All were a head shorter than me. I felt

like a tired, old lioness surrounded by a pack of hyenas. By my

calculation, the ride should be only the equivalent of two dollars in

local Yuan, not their outrageous cost. Feeling trapped I was ready

to accede

From

behind the drivers, I noticed that a young Uighur man was watching. I

saw a sincere concern in his face. He came closer, motioning me to

stay put. After a brief study of passing traffic, he stepped to the

curb and signaled for a private car driven by an Uighur to stop. They

spoke briefly, and then he motioned me to get in the car.

Trusting

in the kindness of strangers I got in.

The

driver had me at the bus station in just minutes, but shook his head

when I offered him some Chinese Yuan. I extended my arms, palms up,

and shrugged in a gesture meant to convey: “Why don’t you

want money?” He smiled and pointed at my dress. It dawned on

me that Uighurs, Uzbeks and other central Asian tribes were Turkic

people who shared a national costume. Wearing an Uzbek striped, silk

dress with Safranesia’s bloomers was like a flag making a

political statement, advertising my sympathies for the repressed,

underprivileged Turkic minorities on both sides of the border who

were dominated by policies of communist regimes in distant capitals.

Dressed like an underdog, I had emboldened those taxi drivers to

treat me like an inferior, but it also got two Uighur men, strangers

to each other, to protect me in a small act of kindness and defiance.

More

than a decade has passed since my travels in that silk dress. The

world has changed. The news reports about muslim terrorism in the

region dominate the news. But all I can think of is the kindness that

was once extended to a lone western traveler

(Unless

you

type

the

author's name

in

the subject

line

of the message

we

won't know where to send it.)

Helene's storylist and biography

Book

Case

Home

Page

The

Preservation Foundation, Inc., A Nonprofit Book Publisher