It was a spring day in Dhaka, the monsoon still some weeks away. Ashraf and I were having tea one day in my office, the usual strong brew – the best leaf from Sylhet – to which he had added three spoons of sugar for the taste that Bangladeshis considered the right, true cha. My own cup made do with one spoonful because, after all, might not three spoons be – in the words of the catechism – an occasion of sin?

But I put this thought aside and asked, “Do you know where I might get an old book rebound?” Ashraf had spent all his life in Dhaka, knew all its neighborhoods and was the best source for information.

“An old book, is it? Well, for this you must go to the Armenian Church. It’s near the Babu Bazar, in the old part of Dhaka”

Having been in Bangladesh for over a year. I was no longer surprised by such a revelation. After all, if Calcutta could have a Chinese neighborhood and a Jewish enclave, then surely Dhaka could have an Armenian church.

“How is that an Armenian is binding books in a church in Dhaka?” I asked.

Ashraf laughed, almost spilled his tea and said, “Of course he’s not Armenian – he’s Bengali, and his shop is next to the church, not inside it! Really, Giles, such a silly question…”

“Forgive me, Ashraf. Somehow I have the impression that mosques are fairly common in Dhaka but churches less so. How did an Armenian church come to be there, and in such an old neighborhood?”

“Well, very long ago – over a hundred years past – there were Armenian merchants in the jute trade, quite a few of them, and they built a church. It’s a fine building and it’s still there. The Armenians did many good things in Dhaka. You have heard of the Pogose School?”

“Yes, I have. Why?”

“It was established by an Armenian merchant for local boys to attend, and he left money to keep it up. Now, of course, all the Armenians have died off but their church remains. But tell me about your book.”

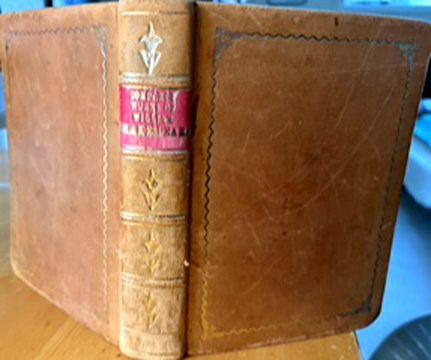

I had it with me at the office that day and I handed it to him. It was a well-worn, tattered volume, a rare treasure I had found some years before in a used book shop in Seoul. The book was old and in a delicate condition and the cover and spine, made of very light leather, were partly detached. The pages were the thinnest paper, almost like tissue. Ashraf handled it carefully, turning some of the pages.

“Shakespeare? Is this really the complete works, in such a small volume? I can see the paper is very thin but is it all here?”

“Yes, all his works are in this one small book. Clearly it was printed as a portable volume that a traveler might carry, and somehow it ended up in Seoul. It has no printing date but someone wrote ‘1920’ in pencil on the title page. Certainly it could be that old. Perhaps it belonged to a missionary – there were many in Seoul in those days – or perhaps an American soldier once carried it, Anyway, I’d like to have the spine and covers replaced.”

“Well, for this job you certainly must have the best person and his shop is across from the Armenian Church. But you cannot drive down there. It is down near the river, not far from the ferry ghat and the streets are too crowded and you may lose your way. I will write the address for you and you can take a rickshaw. Every rickshaw-wallah knows the church.”

And so the next Saturday morning I hailed a rickshaw in Dhanmondi and showed the rickshaw-wallah the address. Like most men of his calling he was dressed in a singlet and lunghi, the skirt-like length of cloth tied up at the waist. When he saw I was going some distance he nodded cheerfully and quoted a price to which I readily agreed. Some people haggled with these men but I could never do this and gladly paid whatever they asked. He invited me to sit up behind, stood on the pedals and soon had us moving down the Azimpur Road to the old part of the city.

The rickshaw is well-suited to a city like Dhaka with its long stretches of wide main roads over a perfectly flat plain, not a hill in sight. There were thousands of these vehicles in the city and the men who pedaled them would take you anywhere at any time, assuming you were not in a great hurry to get there. And in Bangladesh, there was always enough time. Sitting on the high seat behind the driver, I surveyed the passing city with its hodgepodge of buildings in many styles or no style at all, its dense crowds – both people and cattle – and enjoyed a breeze denied the pedestrian. After a long stretch we were stopped by a uniformed policeman at the intersection of the Urdu Road near the Shahi Mosque and he let another tide of rickshaws pass. My rickshaw-wallah took the time to sit back on his seat and catch his breath. He chewed his betel-nut with apparent contentment, then spat delicately over the handlebars.

Soon we arrived at the church and I paid my fare, with something added. The rickshaw-wallah beamed his satisfaction and said some words. My rudimentary bazaar Bengali was aided by his expressive gestures and I understood he wanted to know if I would need a ride back and if so, he was very willing to wait. I smiled agreement.

The church was an imposing structure of dark yellow stone with an arched palisade and an octagonal segmented cupola and pointed dome. Through the gate I could see that most of the churchyard was taken up by a cemetery, a poignant reminder of the diaspora which brought these people so far from their homeland.

The book-binder’s shop across the street made itself known to the public with a large sign in bright Bengali letters, and off to the side one word in English – Books. Inside the shop I took in the smells of leather and glue, overlaid with the pungent aroma of bidis – the small, thin cigarettes made from the harshest sort of weed and smoked by many men, including the old bearded man who greeted me.

I guessed his age at about fifty but the hardships of life in Bangladesh aged people quickly so it was impossible to know. He wore cotton trousers and a panjabi shirt, the usual dress for a man of business. He stood at a wide table with his work and tools spread out before him, and greeted me as I entered. I took the old book from my bag and asked if he could replace the covers and spine. He took the book into his hands with something like reverence, smiled and caressed the old leather.

His English was very good and he amazed me with his first words as he turned to the title page and said, “Ah, the Sweet Bard of Avon!” He knew what kind of book he held, and I could see his interest went beyond the craft he practiced. He thumbed delicately through the pages, “Wonderful paper! So thin, so light!” And then, “Where did you find this?”

“I found it in a used book store in Korea but as you can see, it’s very old and falling apart and needs a new cover.”

“Oh, indeed, you must replace the cover to protect these pages. This is very –how do I say? – fragile. And I’m sure it’s valuable. What kind of cover do you have in mind?”

“I just want the book to last many more years, and I travel quite a bit so it should be something strong. What do you recommend?”

And so began our discussion of different kinds of leather, colors and such. He showed me some samples of his work, including a beautiful Koran he was working on. He said his father had set up the shop and taught him the trade long ago, during the Raj, and he had taken over when his father died, just after Independence from Pakistan. There was no hurry so he ordered tea from a shop nearby. As we drank tea and smoked we discussed repairing the book and after some discussion with digressions here and there we settled on a price.

“If you come back in two weeks it will be done to your satisfaction” he promised me.

I did and it was. He gave it strong hard covers in durable brown leather and a stout binding with the title incised. More than thirty years later I still have it and value it as I do very few possessions. It has managed very well the passing years since then – perhaps better than I.

I look into it from time to time, but today we have digital books that let everyone carry the complete works and the rest of one’s library in a form more portable than my old volume. But of course its value goes beyond the intrinsic worth of the physical book or the timeless literature in its fine, frail pages. It also carries my memories of places where I spent my early years, and the many people I met in those times –a friend like Ashraf, and the old craftsman in the bookbinder’s shop by the Armenian Church in Dhaka.