The wandering, wayward life I led in my twenties and early thirties had consequences, and one of these was a chronic illness. There’s no certainty how this began but I can say with confidence how it ended.

Somewhere along the way I picked up one or more — or many more — microbial passengers, little things who joined me in the course of a meal somewhere and stayed for the free ride. Was it in Chunchon, or perhaps some village in the Korean mountains? Or was it a lamp-lit meal in a dak bungalow on the road north of Rangpur, or a dubious tiffin on the river boat to Khulna? Or perhaps a hasty noodle soup at a roadside stand in Aranyaprathet on the Thai-Cambodian border? More likely it was all of these and more, for these ailments seemed to build on one another, occasionally receding, fading to a minor inconvenience for a few months, then coming back with new vigor.

The symptoms would not bear description in polite company, or any other company for that matter. But however unpleasant it was, I told myself it was nothing. I insisted to myself that I had the digestion of a crocodile, and these were only occasional discomforts — well, in fact, sometimes almost daily episodes — but anyway, it all meant nothing. I was, like everyone my age, immortal, and so I soldiered on.

At one point after ten years in Asia, I passed through New York for a few days and went to see a specialist in tropical medicine. He did a lot of tests and then told me I had amoebic cysts and that there was no particular cure, that I would have to live with this indefinitely and must avoid certain foods, mostly things l liked very much. I was fully prepared to ignore this suggestion — my usual reaction to any sound advice in my younger days — but the decision was not completely in my hands, for I was newly married, an important consideration.

We were living in Seoul then, in the winter of 1981, in a small apartment south of the river. My bouts of illness were frequent and unpredictable and it didn’t seem to matter what I ate. It did no good to explain to my wife that it had nothing to do with what she cooked, anything could bring it on. All this, naturally enough, caused her distress. Something had to be done.

In Asia, no one would be surprised to learn that western medicine could not solve the problem, for everyone knew that the most intractable afflictions called for Chinese herbal medicine. Moreover, I was the last one to assert the infallibility of a Manhattan specialist. And so, on a recommendation from my mother-in-law, who knew a lot about these things, we went one winter morning to Ankuk-dong, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the oldest part of Seoul. It was a neighborhood of ancient houses and antique shops, and it was also a thriving center for Chinese herbal medicine.

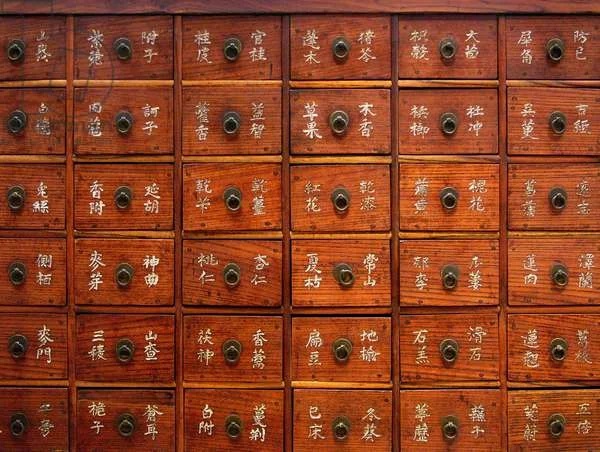

I remember it well and can still smell it like it was yesterday. We entered one of the old tile-roof houses, built in the traditional way. The private family rooms were in the back, away from public view, and the front part of the house was given over to a wide room where the herbalist saw his patients and carried on his business. This room, in effect his clinic, was entered directly from the street through sliding, paper-lined wooden doors. We took off our shoes and stepped up onto the maru, a polished, wide-planked wooden floor. Ranged along three walls were tall wooden chests (called yak-jang), each with its astonishing multiplicity of small drawers and on each drawer were carved Chinese characters naming the contents.

And the smell was wonderful! Or I should say smells, for there were many, many of them, all mixed together, and this agglutination of smells, this consortium of scents was intrinsically nameless. Perhaps a suggestion of ginger? — a stray whiff of cinnamon? — a hint of ginseng, recognizable after a decade in Asia? But there were, I couldn’t deny, other unknowable smells whose true nature I could only guess — bear’s paw, rhino horn, deer antler, and what else? — ‘eye of newt and toe of frog, wool of bat and tongue of dog’ ? The effect of this dense smell was overpowering and still a vivid if unnameable memory.

In contrast to the mystery of these smells, the examination was straightforward and not so remarkable. The doctor, an ancient gentleman, lean and tall, his angular face underscored by a wispy beard, had me lie flat on his table — no need to remove my shirt, but I might loosen my tie — and then he began to palpate my abdomen, a long, slow process. There was no notion of lab tests, no sample of blood or any other fluid, and I suppose there was no need. In this place, science and art were a zero-sum game, more of one meant less of the other. He had no stethoscope but I had the sense that his fingers not only felt but also listened, and occasionally he would put his broad palm down and press hard — perhaps seeking something deeper? I started to ask a question but he insisted on silence, and continued until he seemed satisfied.

After all this, he told me I had parasites, which was no surprise, but then he said with no hesitation that he would give me medicine that would eliminate them, and he spoke with no equivocation and every appearance of confidence.

Then he spread on the table a dozen or more square sheets of paper, each about a foot across, and he began to fill each with an assortment of dried herbs and other plants (or at least I assumed they were plants — no obvious newt’s eye) which he took from the little drawers in the yak-jang. I had no idea what any of these were. Moreover, he made no precise measurement of any of these ingredients, and I could only suppose that he knew by touch or sight how much to use. It brought to mind the ancient European apothecary measurement of a scruple, the amount you could grasp between thumb and one finger, or so I seemed to recall. There were perhaps a dozen ingredients in each square, and when he was done he folded each one artfully into a neat package, then all of these went into another neat and artful bundle. He then told my wife how to prepare each package into a daily dose which I must take for two weeks — precise instructions on how much water to boil and how long to let the dose steep, and she must use a special covered earthenware pot. I must drink half of this dose after breakfast and the rest later in the morning, and I might take this with me to the office as long as it stayed hot in a thermos.

And so I began my experiment with Hanyak, the common Korean word used for Chinese herbal medicine.

I had the first dose next morning and, to say it charitably, it could only be an acquired taste. It was the color of strong coffee but with no other resemblance. The brew was bitter, with an underlying hint of ginger, but perhaps this was meant to cover a more disagreeable taste. Later that morning, at the office, I opened the thermos and poured out the rest of the day’s draught. My Korean colleagues were surprised, and then delighted — just think, an American taking Hanyak! Who ever heard of such a thing! But then I explained my problem and they were very sympathetic — of course my wife would be worried and she would certainly know what to do — they, too, had taken Hanyak for whatever ailed them, always to good effect — everyone knew Ankuk-dong was the best place for Hanyak— expensive, yes, but what does that matter if the problem is solved?

And in fact the problem was solved. Within two weeks — and with no side effects or any discomfort and indeed with the dose tasting better each day — the problem which had bothered me for so many years was gone. And it never came back. I could now eat whatever appeared before me with no misgivings and, most important, with no distress to my wife. It’s the least a fellow can do in the interest of domestic harmony.

All of this was thirty-odd years ago but I think of it now and then, and it seems to me that East may meet West in many ways, and it may happen that one may learn from the other, and when this happens it may leave behind an episode, a memory, a story to share years later.

February, 7, 2018