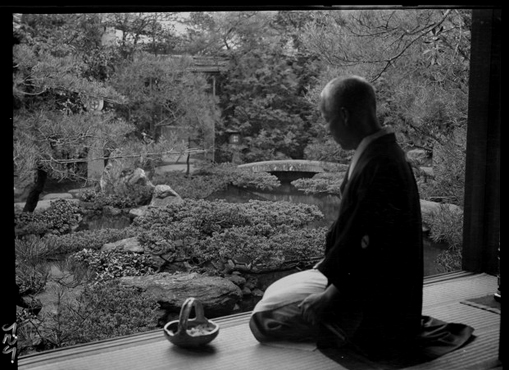

Autumn 1971

This Chinese

character, (commonly used in written Korean), means Autumn.*

Giles Ryan

© Copyright 2024 by Giles Ryan

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

|

Autumn 1971

Giles Ryan © Copyright 2024 by Giles Ryan  |

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |