Cheers

To Those Who Cocked A Snook

Ezra Azra

.

©

Copyright 2024 by Ezra Azra |

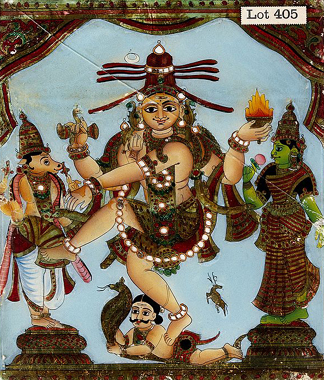

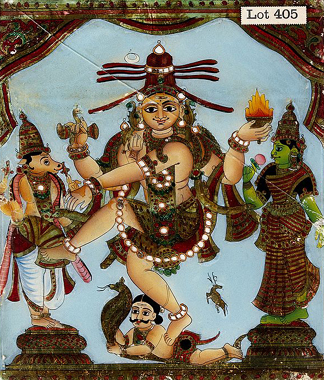

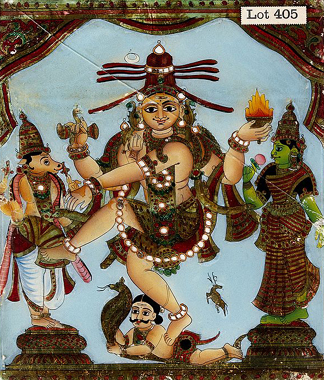

A Hindu deity. Gouache. courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

|

It

happened in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the small

utterly nondescript village of Kottarakkara, in the State of Kerala,

India.

By

then India had been a part of the British Empire for nearly a

century.

Both

of our protagonists were in their early teens. He was a penniless

Christian; She was a wealthy Hindu of the Brahmin Caste; the highest

Caste in India.

Nobody

knows how many Castes there were in India in the nineteenth century.

The lowest number suggested was five; the highest number was

thousands. Everybody agreed the highest Caste was Brahmin. Those born

Brahmin were believed to be genetically inclined to being

intellectually superior to others.

The

gods punished anyone who did not obey Caste rules.

Christianity

had come to India eighteen

centuries earlier. From the beginning, Christianity and all other

non-Hindu religions, were regarded as lower than the lowest Hindu

Caste.

Our

Brahmin female protagonist had been born with a defect that forbade

anyone from marrying her.

In

Hinduism in those days, to be unmarried, in any Caste, female or

male, was the worst curse from all the hundreds of Hindu gods. A

primary righteous obligation the gods expected of a person was that

they should be kind to other righteous persons. Persons were exempt

from this obligation in their treatment of unmarried individuals.

Multiple spouses was a Hindu remedy that rescued unmarried family

members. In order to protect the family from the shame, already

married members, female and male, were allowed to marry family

members who were not married.

Hindu

females unmarried in their late teens, and without marriage offers

from male family members, were encouraged to commit quiet dignified

holy suicide by drinking one of many homemade poison brews. The

elaborate ceremony by which this process was celebrated was among the

holiest of Hindu poojahs, attended by many gods. It was a sacrifice

holier than sati, which was a widow’s sacred immolation by

leaping into her dead husband’s cremation flames.

An

unmarried female who graciously accepted such holy self destruction

would be highly honored by all gods in the life hereafter. Many, many

of the minor immortal Hindu gods would be honoured to worship her in

the life hereafter.

Occasionally,

there were rumours of a Hindu converting to another religion in order

to escape the Hindu brew offer of nirvana. For obvious reasons, such

unspeakable individuals would be vociferously and loudly publicly

disowned by their Hindu families.

It

was normal for rich high-Caste people to employ poor low-Caste

people to do domestic work. In those days, the belief among Hindus

was that the gods favored high-Caste persons who were brave enough to

risk unholy contamination by allowing low-Caste persons to do menial

work around and, even, inside the home.

Our

female protagonist had four siblings. Her two elder brothers were

married and had their own homes. When they visited with their

families, She was expected to confine Herself to Her room. Because of

Her, their visits always lasted only minutes.

Her

two sisters were younger than She. Both were already betrothed.

The

time was fast approaching when She would be offered a choice of those

Hindu spice-tasty homemade holy poojah brews.

It

had been months our male protagonist had been hired to attend the

family’s acres of garden around the home. His remuneration was

generous amounts of food, so much food that He was encouraged to take

most home to share with His poor Christian family.

The

astounding mystery was why that Brahmin family had hired Him, in the

first place. They knew He was Christian, and that because He was

Christian no Hindu god would look kindly on them for hiring Him.

A

likely reason was that whereas there were no rules from the earliest

times that specifically declared Hindu gods were offended by the

suggestion that there were gods of other religions, there being no

other religions in those earliest times. And so, there was no

definite contamination suffered by a Hindu who, even accidentally,

touched a non-Hindu.

Another

likely reason was that since Brahmin payment in money to a

non-Brahmin servant was unthinkable at all times, the payment in

left-over Brahmin food to any pukka Hindu of a lower Caste was

downright blasphemous.

The

most likely reason was that in a small utterly nondescript village

such as Kottarakkara, supremely pure highest Caste Hindus could

commit minor sacrilegious deeds, and suffer no holy repercussions.

And

so, all the times He worked in the garden, that Hindu-cursed Brahmin

female was allowed to take food to Him and to place the containers on

the ground out of sight away from Him. He was never aware of whom it

was who brought Him the food. He was never curious because He had

assumed it was a high-Caste person who would not care to be seen by

Him. And if He saw that high-Caste bringer of his food, He would be

considered insolent; and so He would not be allowed to work there,

ever again.

Hence,

when one cloudy day He saw Her waiting where He went to eat His food

where it had been placed, He was so shocked that His body, virtually,

turned to stone; refused to obey His panicked thoughts to turn and

run away for his miserable life.

Of

course, He could never have known She was Hindu-cursed. Perhaps, just

perhaps, had He known, there might not have been so much terror in

his reaction at seeing Her so close to Him.

While

He stood as still as a stone, She came up to Him and placed Her hand

on His shoulder. In sheer terror, with perspiration dripping

copiously from the top of his head down his forehead and blinding his

eyes, and down the back of his neck, He fully expected to die

instantly.

She

whispered to Him, “Will you marry me? Please?”

Instantly

involuntarily He nodded slightly, fitfully; not because he understood

her question. Not because it was always safer to agree nonverbally

with any question from a person of a higher Caste.

He

nodded, only to get Her to leave Him alone. His nod was mostly a

shiver of abject terror She quite misinterpreted.

She

whispered, “Say it. Please!” It was hoarse and barely

audible when He replied, “Yes.” She left.

He

fainted. He felt Himself collapse to the ground, in slow motion.

Within brief minutes he recovered. He hastily mopped away the

perspiration with a perfumed large exquisitely embroidered

purest-cotton handkerchief he was clutching in a hand. It did not

occur to Him to question the presence of the handkerchief, even

though He had never in his life owned or used one, perfumed or other.

In

the days that followed the fear that triggered his traumatic

temporary loss of consciousness, gradually, fitfully, gave way to

joy. He was far too young to know just how impossible their marrying

was at that time in Caste-infested India, and in Caste-infested

Hinduism anywhere else in the world; just how violently fatal Caste

and her family would have made it for both of them.

In

the days that followed, He caught glimpses of Her placing His food on

the ground, glimpses that happened because She contrived them to

happen. He was fearfully puzzled why She had become so suicidally

defiant of Her religion; of Her gods; of Her highest-Caste family.

Unexpectedly,

He found out why, in a few days.

Her

mother, unknown to Him, had been seriously ill for days, and died.

That thoroughly Hindu highest-Caste home was plunged into near-chaos.

There

was a constant stream of Hindu persons coming and going, most of them

being distant family. Others were associates and strangers eager to

be seen paying their respects to the numerous wealthy living, as

eagerly as to the dead mother of five.

What

He would never know about was that deeper drive that gave that

Brahmin Hindu girl the outrageous courage to propose to Him,

who, on account of His being Christian, was lower than the lowest

Hindu Caste. It was Her dying mother’s words spoken especially

and only to Her.

While

Her mother lay in bed dying, Her family forbade Her from being at

Her mother’s side. They opined She had already been enough of a

curse all Her life to them and to Her mother for being

unmarriageable. She had cunningly contrived to

attend Her

dying mother for a few seconds. Her mother had clasped Her hand,

whispered words to Her, and kissed Her hand. It was those words that

ignited an utterly and wholly unHindu daring courage in Her. With

some of those words Her mother gave Her directions to a pillowcase

filled with pure gold jewelry, many times more than enough to pay a

king’s ransom.

In

addition to the quite fortuitous family turmoil brought about by the

mother’s death, there was the national unrest India was being

subjected to by the politicians’ incitement of the people to

march for independence from the conquering Christian British Empire.

That

conquest had never seen peace all over the country at any time.

Our

protagonists, He and She, saw an opportunity.

They

joined one of the many peoples’ rowdy anti-British marches. For

the first time, our protagonists held hands. For the first time,

because He saw the twin in Her hand, He knew where that handkerchief

had come from, with which He had mopped away from His face, scalding

perspiration of fear.

For

the first time, they dared to hold hands. Nobody noticed. Everybody

marching, and chanting anti-British slogans could not care less.

Our

protagonists marched for India’s independence from the British

Empire long before the great Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi marched; long

before the indomitable Jawaharlal Nehru.

They

passed a building with a notice about times and nearby places to

enlist to join British Government transportation to other parts of

the Empire, as laborers. They signed up, as husband and wife. They

were ecstatic to be leaving India forever the very next day aboard a

ship, “SS Karanja Pride,” British built and British

driven.

There

were hundreds of emigrants like them on that “SS Karanja”

steamship, headed for British Empire harbours on the East coast of

Africa. Our protagonists kept up their appearance of being penniless

and lowest Caste. In actual fact, much to His infinite joy and

greatest admiration, when She had fled Her home to Him after Her

mother’s death, She had remembered to flee wearing all Her

dying mother’s gift to Her of that pillowcase of gold jewelry.

Decades

in the future, our protagonists died in peace in old age in Durban,

South Africa. He on 5th June, 1949. She on 1st

August, 1973.

She

had never divulged to Him the dying words of Her mother; only because

She never trusted She could have adequately interpreted Her mother’s

poetic words from Her Indian language into English. She trusted one

of their grandchildren who became a school teacher of, among other

subjects, verbal poetry. That grandchild translated their

grandmother’s dying mother’s words into perfectly rhymed

English iamb: “In death is victory for all eternity against

the countless evils in command in this reality.”

The

words were carved in the granite tombstones of both grandparents.

Our

protagonists had five children; all daughters; all adopted from

fellow India emigrants in Durban. He and She lived to enjoy the

company of their thirteen grandchildren, all without Caste; all

without gods.

He

and She not caring to get married throughout their happy lives

together, could have been interpreted as their, verily, cocking a

snook at the hundreds of gods in India, Hindu and Christian, all of

whom, brazenly and openly, forever and forever, could not care less.

Contact

Ezra

(Unless

you

type

the

author's name

in

the subject

line

of the message

we

won't know where to send it.)

Ezra's

Story list and biography

Book

Case

Home

Page

The

Preservation Foundation, Inc., A Nonprofit Book Publisher