Dawn of Dreams

Ruth Ticktin

© Copyright 2019 by Ruth Ticktin

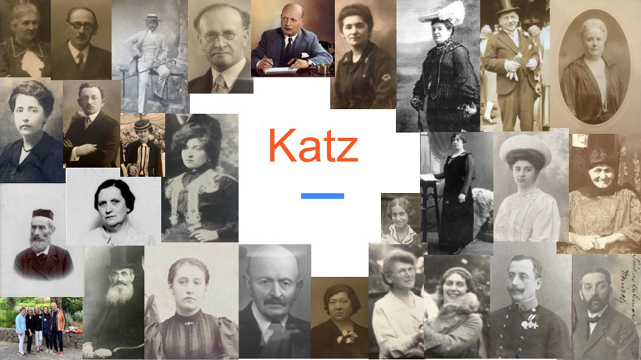

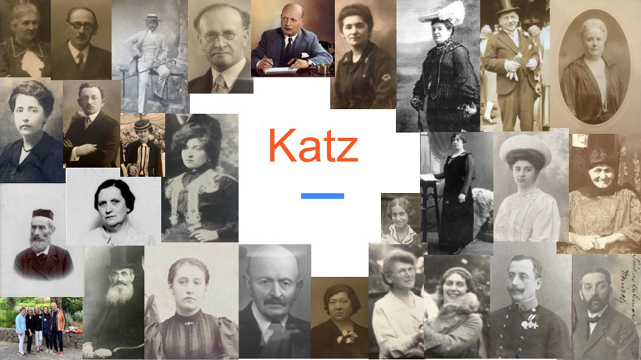

Photo collage of Katz family courtesy of Matt Stein.

Dawn of DreamsRuth Ticktin © Copyright 2019 by Ruth Ticktin  |

Photo collage of Katz family courtesy of Matt Stein. |

To paint the picture, placing people in time is easier than identifying names of locations which continually change. Further complications are the numerous first names, changing last names, spelling variations and the distinctive languages. As Jews in the 1800s many in my family had two names. One was a secular name in the language of the country where they lived and they also had names in the Hebraic language of their ancestors. Most people had last names, or surnames, at this time, but not everybody. People were known in the traditional sense, as the son or daughter of their father’s name. Last names could originate from the place of birth, the occupation of the parent, or initials of the role in the community.

One example of initials becoming a name is using the consonants K and Z. The K was for the word Ko-hen, the tribal role designated to leaders of the priestly blessing in the times of the Temple. The Z is the first letter of the Hebrew word Zadik (pronounced Tsa-deek) meaning righteous. The vowel that appears between the K and the Z is A, and the name Katz in the Latin alphabet became a common surname with some varieties in spelling. My 2nd great grandpa was Jakob Katz.

Jakob Osias was known in Hebrew as Yaakov Yehoshua. The meaning of both Osias and Yehoshua is salvation. Jakob Osias became a Rabbi and was given the title Rav Yaakov Yehoshua and the last name Katz. Many children in the generations to follow were named Jakob Osias in memory of the learned teacher Rav Yaakov Yehoshua Ha-Cohen, who died in 1756. A century later, Sofie, Jakob’s youngest daughter and my great grandma told her children that her father Jakob was from an esteemed family of a great Rav. Two of Sofie’s children to survive and have children of their own told their children who related this lineage lore to their daughters. At that point, the family had pretty much lost the name Katz, forgotten the stories, and were no longer carrying on the traditional rabbi occupation nor priestly roles in the temple or orthodox community. However, the meaning of rabbi is teacher and all of us offspring from Jakob and Malka’s lineage have become an impressive composite of educators. Subsequent descendants were guardians—parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and cousins—teaching their families. Our family are deep believers in life-long learning, educating in classrooms, theatre, business, community service, health, and manufacturing.

Jakob

Osias wife was Malka Reice. Malka means queen and her parents

believed that she was special when they bestowed the name unto her.

Reice, Malka’s middle name, means secret, in the ancient

Semitic language of Aramaic. Her name is a secret, among the many

facts that will never be confirmed. Malka is a name derived from

Amalaka or Amalia, which is Hebrew for

God’s

work. In the area of Europe from Italy to Romania, Amalia became a

popular name and so the grandchildren of Malka became Malki, Malia,

Marta, Amalia. Malka and Jakob believed in educating their girls as

well as their boys. The opportunities were certainly not equal in

their day, but Jakob and Malka managed to instill a belief in learning

for their sons and daughters. Their daughters learned to manage the

shop while their husbands studied. The granddaughters had better

opportunities for secular schooling.

Jakob was born circa 1805 and Malka was born around 1815. They were married in approximately 1833 and, over the following two decades, had eight children who survived infancy and grew into adulthood. The family lived in a small village called Stryi (or Stryj,) and later moved to Zurawno (or Zhuravno.) The spelling of the villages depending on what country and what language was the empire of the time. The village of Stryi is 38 kilometers from Zurawno. That distance when travelled by horse and wagon took them the better part of the day. We can assume that didn’t often make the journey, though others did. Their children would travel between the towns and their grandchildren voyaged even further. Both villages are now part of the Ukraine but were then in the Kingdom of Galicia.

In the 1840’s when Jakob and Malka were having babies, there were a few thousand people living in each of these towns. Most the villagers were Jewish, a peak of 2,000 in Zurawno of the 1880s. Three hundred years before that, Zurawno had been ruled by kings who fought the Polish and Turkish invasions. Like the rest of the area, the village was located on a tributary, close to a river, the source of commerce for the region. A bridge crossed over the Dniester River a mile from the town square where the market was located. The air was always healthy in Zurawno, which could have accounted for the family’s survival. A sanitarium for children suffering from tuberculosis operates today in the town, proud of its superior air quality.

An ancient palace in the village park still sits next to a 400-year-old oak tree. Jakob and Malka’s third-great-grandson dreams of going to Zurawno. He thinks he will take a rest under one of the grand trees that was alive in the mid-19th century, and there he’ll talk to his ancestors.

The village had successful shops and a marketplace where many of the Jewish people worked. There were houses of prayer, Hebrew schools, and Jewish clubs. Most likely Malka and Jakob had the jobs of merchant and Jewish teacher, respectively. The dynamic being, the woman ran the shop and the man studied the Bible and Jewish laws, as continued in the next generation.

One by one the children went off to other close-by towns and villages, north and south of them, and began to raise their own families. They all stayed within the same western region of the Ukraine, (or northern tip of Romania) until many of the children made the big move to Vienna. They lived in the Carpathian mountain-valley region, called Galicia, which was once a kingdom of its own. Galicia became a part of the land of Ruthenia, Poland, and Austria-Hungary. In Jakob and Malka’s day, Galicia was part of Austria, somewhat autonomous, and divided by tribes more than by religions. They would speak of the places where the Ruthenians lived and worked, the homes of the Israelites, the Polish regions, the royal residences, and the areas of the Roma. The section of Galicia where they lived was defined at least for them, as between Vilyunychi, Poland the northern border, and Itcani Suceava, Romania to the south. The region is geographically known as the Outer Eastern Carpathian Mountains.

Snaking down from the heights of the mountain’s ridges was the Stryi River and towards the end of the river was the town of Stryi. The first three of Jakob and Malka’s children were born in the town of Stryi, Ukraine. Around 1840, the family moved east to Zurawno, several hours riding horse and buggy, for the birth of the younger children. Malka may have moved back again twenty years later because there was more schooling and work in the larger town of Stryi where more of her children were living. Before the children began to move away, heading west, all of the eight siblings had children of their own. Some of those children were born in Galicia, some in Vienna, and some in England. Several of the cousins grew up together in Galicia and many reconnected over the ensuing decades of chaos and relocation. Jakob and Malka’s fifty grandchildren, who survived infancy, were first cousins. As many as twenty of those first cousins lived at some point in Vienna.

Towards the end of their child rearing years, Jakob and Malka understood that their children would be spreading their wings further out than they themselves had ever dared. And who knew about their grandchildren, but this was a change that they welcomed with hope. Their neighbors had been predicting a doomsday with wars, escape, and disease lurking on the horizon. The situation in their towns was going to change and the families would be forced to flee from their comfortable homes where they’d lived for hundreds of years. Jakob and Malka prayed that their lives would not be adversely disrupted, or at least not to a great extent. They listened to the neighbors’ fears and sighed, taking misfortune in stride, come what may. Looking into each other’s eyes they were strengthened. If there was one thing they’d learned, that was to graciously accept their powerlessness.

“Whatever happens, we have each other. We will teach our children about the good within us. We must nurture the divine graces of our lives.” Malka said and Jakob responded,

“Let

us raise our heads to the one on high. Go forward, always with the

protection of Adonai of our ancestors.” And the children will

always remember the words of Jakob and Malka.