The Real Ireland

M. D. (Peggy) Roblyer

© Copyright 2024 by M. D. (Peggy) Roblyer

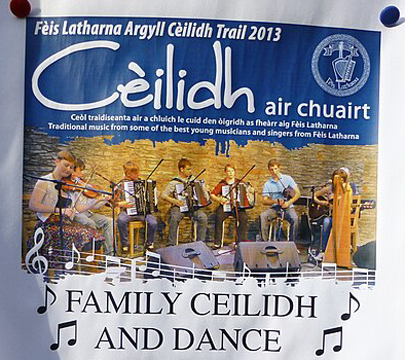

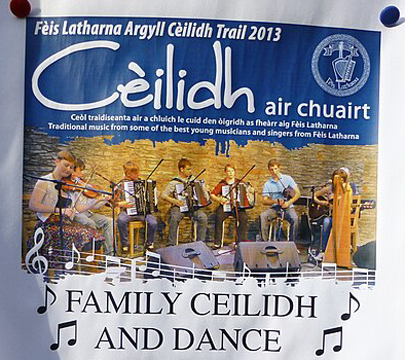

Photo by Kenneth Allen at Wikimedia Commons.

The Real IrelandM. D. (Peggy) Roblyer © Copyright 2024 by M. D. (Peggy) Roblyer  |

Photo by Kenneth Allen at Wikimedia Commons. |