The

Devil's Torch

L. H. Rhodes

©

Copyright 2011

by L. H. Rhodes

|

L. H. Rhodes

©

Copyright 2011

by L. H. Rhodes

|

|

The 231st Engineer Combat Battalion, under the command of Colonel Ira M.F. Gaulke, had been in the Nevada desert for two months, living in twelve-man squad tents, building the camp that would be called “Desert Rock.”

It was mid-November 1951, and the United States Army and the Atomic Energy Commission were preparing to test the ability of men and machines to move through Ground Zero within minutes after the detonation of an atomic bomb.

I was a corporal in Headquarters Company, assigned to drive the Executive Officer, Major Oren Fayle.

His position quite often required us to be in the forward area, called Frenchman’s Flat, so I had the opportunity to watch the preparation. The first shot would not involve live troops. A variety of military equipment including jeeps, trucks, tanks, personnel carriers and halftracks would be used.

Some would be dug in to various depths and distances ranging from two hundred yards to three miles from ground zero, while others would be left completely exposed. Heat, blast and radiation sensors would monitor each vehicle. The shot was scheduled for eight a.m.

This would be the first test since the construction had begun on Camp Desert Rock, and the 231st Engineers were invited to witness the spectacle.

First Sergeant Meager rattled us out of bed early that morning. Breakfast would be at five a.m. and no one needed a second call.

The squad tents were pitched over wooden platforms to keep the cots and men from sitting and walking directly on the ground. But the cracks between the boards and the entrance flaps on the tents provided easy access for a variety of desert fauna. Scorpions and rattlesnakes were the most serious intruders, and no one pulled on a boot before banging it against the rails of his cot to dislodge unwelcome visitors.

The chow line was alive that morning. We were young, healthy and excited. Especially excited. We talked more than we ate, but the coffee was hot and strong, and even the KPs were grinning. By six a.m. the area was secure and the trucks began to line up for the ride up to Frenchman’s Flat. I got my jeep and picked up Major Fayle. We would lead the convoy into the forward area.

None of us had any idea what to expect. All of us had seen the newsreel films of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but this was the real thing. We would be among the very, very few human beings to witness in person the unleashing of the most powerful force the world has ever known.

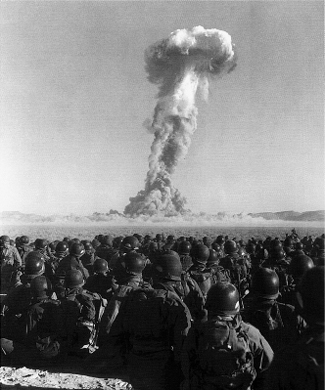

Forty minutes later we reached the observation area three miles from ground zero. The tower wasn’t visible from this distance, but we all knew where it was. The entire battalion of over four-hundred men fell into Company formation and platoon leaders from each Company accounted for every man under their command. It wouldn’t do to have stragglers wandering around out here.

A truck pulled up and Loudspeakers covered each Company as a representative of the AEC began the final orientation. Because there were not enough safety glasses for everyone, all of us would have to face away from ground zero until we were told it was all right to turn around. He explained that at detonation the fireball would be brighter than the sun, and to look at it was to risk permanent blindness. We were invited to sit down. He told us that anyone silly enough to remain standing would be slammed to the ground by the outgoing shock wave. It would continue to expand until it hit the mountains and it would bounce it back. The return shock wave would not be as powerful as the outgoing, but no one would be able to stand against it. Soldiers don’t question; they obey. Our attention was total. No one spoke during the entire dissertation. We sat and faced away from the tower. My watch said seven-forty. Twenty minutes to detonation.

An airplane passed overhead. It was a last minute visual check of the area, and more importantly, a final check of wind velocity and direction aloft. Any significant deviation from predetermined patterns would cause a delay, and the slightest wind shift toward Las Vegas, 65 miles away, would cause the shot to be aborted.

The desert floor came alive with conversation and laughter as the troops vented the tension which swelled within them. The minutes passed and the conversation lessened until the final countdown began. In our total silence we heard…ten…nine…eight...

At the count of zero, terrible thunder roared behind me. Within seconds the outgoing shock wave bent my head into the ground between my feet. Then the loudspeakers crackled over the echoing din, “You may turn around now.”

As one, four-hundred soldiers swung around.

The huge fireball appeared to be only a few feet off the ground. It was brilliant, and as red as the setting sun. It shimmered, vibrated, pulsed like a beating heart, then suddenly it shot upward with furious power, disappearing into the smoke and sand and debris of the explosion.

The return shock wave hit me. It felt almost as powerful as the outgoing blast, no matter what the AEC agent had said. I had forgotten about it and it was a good thing I hadn’t stood up.

The cloud rolled and rolled and rolled within itself, rising like the trunk of a giant gnarled tree bursting from the ground. It rose higher and higher, then the mushroom top began to form. I remember the darkness of the cloud. Not the billowing white shapes of a summer day, nor even the dirty gray of the impending storm. It was dark, the darkness of evil, the darkness of death. It was truly the Devil's torch.

As the mushroom swelled, the heat from it condensed moisture from the air, and it froze instantly into ice crystals as the mushroom cloud rolled and boiled like a witch’s cauldron.

We sat on the desert floor for nearly an hour, watching the huge cloud drift. At last it separated from the stem and began to dissipate. Powerful winds started pulling it apart.

Finally, then, our voices returned and we were able to speak above a whisper. The force and intensity of the explosive release of the energy stored within the tiny atom is beyond belief. No newsreel, no television tape, no photograph or painting begins to capture the absolute power and fury of it.

The experience gave birth to the only poem I have ever written, and it was only after the Federal Government informed me thirty years later that I could be at risk for cancer from radiation fallout from the four shots I witnessed from only a few miles away, that I put it on paper. Here is that poem. It is called, “the Choice.”

The Choice

In the void of space,Contact

Lloyd

(Unless

you type

the

author's name

in

the subject

line

of the message

we

won't know where to send it.)