Robert Flournoy

© Copyright 2023 by Robert Flournoy

|

This

Is For My Coach

Robert Flournoy © Copyright 2023 by Robert Flournoy  |

|

In August of 1957, the call went out to all ten year olds in the neighborhood that a little league football team was being formed to be a part of an already established league. New housing developments were springing up all over El Paso, Texas (popping up in every town in the nation, actually), and with each one came new sports teams for the baby boomers whose parents were moving in. I was ecstatic, beside myself. I had always been the fastest kid in every school I had attended, loved rough, and tumble, and saw the grid iron as a playground of absolute glory. I was born to bury my first cleats in its grass, and live the stories of my father, and his brothers, all of whom had played at Auburn in the 1930’s and 40’s. Baseball had been my only organized sport until then, but my heart, mind, and soul had always been pre occupied with football. I was crushed, dispirited, and weak when my father informed me that I would not be playing due to the fact that young boys were not developed enough physically to play this game, and that lifelong injuries could be sustained. No football until high school was the ruling. I spent the next 3 years watching my friends play, in their orange jerseys, with T’s on their helmets, under the lights, with girls on the side lines, having the time of their lives. I had outrun every single person on that team on the playground, they knew it, and were perplexed why I was not out there with them. Those were the years that my father’s PTSD, something completely unknown to the world in those days, started to manifest itself through violent mood swings, and alcohol abuse. I learned to go numb, at home, and while watching my friends play football, denied more of my child hood than I would understand until many years later. My own war in the late 1960’s would help me better understand the impact on my father of his two, but I never forgot those soft Texas autumn evenings, under the lights, on the sideline.

In the fall of 1959, with the Texas youth league in full swing, my dad, an army officer, was ordered to Germany. The family was in high spirits faced with this great adventure, off to live in Europe for three years. My dad painted grand pictures of glorious vacations in Italy, France, and Spain. My mom was aglow. I was deflated, as I had secret plans to walk onto the local high school football field in three years. I attended I attended all of their games, often with my father, where he would point out the stars, and the techniques of the players. I was in a constant state of hurt for having to wait, but I loved my dad fiercely, and kept that part of me bottled up. When I asked about football in Germany, my dad told me they played soccer. He extolled the virtues of that game, which I would be allowed to hop right into. I was not listening. I had just won the city 50 yard dash championship for 12 year olds, and did not want to leave behind my dream of playing football for Burgess High School.

We arrived in Ludwigsburg, Germany in November of 1959. I was 13, and in the seventh grade. We moved into a military housing complex that was to prove to be the equivalent of any small town in America, complete with schools, churches, shopping, movie theater, and, an interesting place called the AYA (American Youth Activities) where children could gather to play pool, ping pong, dance, and generally be kids, isolated from the economy of post war Germany, which surrounded us, but was not really a part of our world. They called this little village of ours Pattonville. It was actually several dozen streets of 4 story apartment buildings which faced each other across a common road. Very cozy, very intimate, and supportive of instant friendships, especially at our age. I made several friends quickly. I was pretty stunned to find out that they had just finished their little league football season. All throughout Europe, where American forces were stationed, there were AYA’s that supported teams in basketball, baseball, and football, for kids who were 15 or younger. It was assumed that high school sports could take over from there. I was glad their football season had just ended, and deliriously happy that baseball, and basketball teams existed, but black, already, with despair about my prospects of being able the join these boys, who would become my closest friends, on the football field when we were 8th graders. The not unpredictable bombshell was dropped by my dad soon after our arrival in Pattonville, that I could participate in the AYAs sports activities, (meaning baseball, and basketball), and special events, like dances, but could not actually go there to hang out. That close proximity of young teens, of all races, and ethnic backgrounds, sons and daughters of officers, and enlisted alike, was too much for my Alabama native, depression era raised officer father. The numbness returned. So did the family demons, from time to time, which knew no continental boundaries.

In the winter of 1960, my dad took the family on a ski week end to Garmisch, a resort in Bavaria that had once been a big Nazi ski, and winter recreation area. The American military had taken it over for the use of U.S. families. It was a magical winter wonderland, and I was introduced to skiing. With the reckless abandon that all boys have, I did not understand that going fast downhill on skis was a lot easier than stopping. On my first run down the side of the Zugspitz mountain, I broke my right leg in 6 places, in what my mom described, as a beautiful cart wheeling Ferris wheel dance that ended abruptly in a snow bank. She thought I was fine because of all that snow. I wasn’t. And, I would never be quite as fast on my feet again, after 3 months in a cast. But, I got rid of that cast just in time for my first AYA team experience; baseball.

But, this is not about baseball. It is about football which started in August and the air of excitement that gripped my group of friends as it was revealed that a new Pony League football team for 14, and 15 years olds, with a 150 lb weight limit, was not only being formed by our AYA, but by AYA’s across Germany in what would be known as the Nekar Valley League. I was sick with dread. And when my best friend, Bob Newman told me his dad, who had considerable experience, was going to be the coach, I dejectedly told my father what it meant to me to be able to play. Hell, I was in Germany, and could not even go to the f#@*! AYA with my buddies. Please let me play football with them. With some gruff pontificating, and snorting, to include the observation that Captain Newman had played at Iowa, as opposed to Auburn, so he probably didn’t know jack shit about the game (eyes twinkling). He melted me with his approval. He would never miss one of my practices if he could help it, or, God forbid, a game. My whole life changed. I was one of the boys. I was going to play football. And, true to form, my dad was to quickly point out that he had let me play because he knew in his heart that I would be well coached, loved, and safe with Stewart Newman.

We

met that first day on the old soccer/ baseball field behind the AYA.

An assortment of kids, white, black, brown, yellow, all from the

families of our soldiers who lived in Pattonville. Some were 150 lbs,

some 90 lbs. Some had played for years on youth league teams, but for

most this would be a first football team experience. The logistics,

organization requirements, parental

concerns,

teaching of basic skills (what is this? A chin strap) must have been

an enormous undertaking for Coach Newman, but I never remember seeing

him flustered, or up tight. Always a big smile, the supreme leader.

Our initial uniforms were very old, baggy pants, scarred up helmets,

many without facemasks (remember, 1960), and, drooping cardboard

pads. But, we were shown a photo of the uniforms that our army unit

sponsor had ordered. Gold, and black! We would be the Black Knights

of The Nekar! Every day, “coach, are the uniforms in,

yet?”….“You have to earn them, knucklehead!”

“Yes sir!”, and we would proceed to learn the basics of

our offense, how to block, how to tackle, and we gradually learned

who would make the team click. Who was fast, who was strong, who was

fearless, who had a temper, who was afraid, who was really

competitive. Our first day in pads we lined up for tackling practice,

and I can tell you that there was trepidation in the air. The kids

with experience were looking at kids who were now bigger, and the new

kids did not know what to expect. Coach announced that we would

commence with a “head on tackling drill”. Oh, shit, I had

heard of such a thing, and it did not sound good. Head on? Very

ominous. “Flournoy, on the ball, Clayson, get out here! 8 feet

apart! Flournoy, you will charge at Mike with the ball securely

tucked, like you are going through a hole in the line, and Clayson,

you will meet him head on, and knock him on his butt! Swerving, or

sliding off to the side is not allowed! On three, go! Hut, hut, hut!”

Five steps later the lights went out. For both of us. We took the

head on thing literally, accelerated to top speed, and made damn sure

that our helmets met squarely, low to the ground. When Mike and I

reunited 40 years later via the miracle of the internet, this head

explosion memory that we had shared so long ago was the first thing

out of both of our mouths. I remembered stars (so did Mike), an

expression of absolute stunned surprise on coach’s face, and

the melting away of several players who had been standing in line,

never to be seen again on the storied fields of the Ludwigsburg AYA.

Coach said, “you guys will do. You will do just fine.” I

could not have been prouder. Later, Bob, coach’s son, told me

that I had taken the head on thing too seriously, and had set a

really bad example for our tackling practices going forward. I

believe I was in complete agreement.

We struggled, and gradually became a team, learning the difference between offense, and defense. We learned a cross buck, belly type offense, and our quarterback, Mike Day, a quick, smart, competitive half French kid who had never before picked up a football in his life, but could throw a perfectly tight spiral, became the heart of this unit, skillfully directing quick broken field running half backs, huge (to us) menacing full backs, and throwing pin point passes to our sure handed ends. We had, we thought, a nicely balanced attack. Our defense, which would become the hall mark of our team in the next two years, was small, but very quick, and coach capitalized on these traits by designing defenses that were variations of the standard 7 Diamond, 6-2-2-1, and Gap 8. We lined up 4 -4 -3, 3-5-3, whatever, stunted, crashed, gang tackled, and swarmed. We lived for scrimmages, and thought we could beat the world. Reality knocked when we took the field against another team for a quarter in a jamboree that featured half a dozen teams from around the league, in our old ragged practice uniforms, because the promised suits of gold had not arrived.

We squared off against a team from across town, Patch Barracks, that would become our hated rival. Hated because they tromped us pretty good on that first ever short meeting. They were bigger, and more experienced, and because we went to the same school with them, they knew we were pretty green, and new to the game. We were shell shocked, and disappointed, but had now eyed the camel, smelled the smoke, and heard the muskets. We were ready to regroup, learn from the experience, and I vowed to get even with a Patch player, Chuck Mabe, who had gouged at my eye in a pile up.

And learn we did, starting at the next practice, when Coach Newman sat us down and proceeded to tell us what we had not done right, what we had done right, and how we were going to address our inexperience, and mistakes. He said it with such confidence that we just knew that it would happen. Our ends learned to box against the sweep that those bastards had used so effectively against us, and our line backers learned to parallel the scrimmage line, committing to a runner only when he made his up field move. Our defensive backs learned to come up fast to meet the play, and never, never, never let an offensive receiver get behind them. We were given very quick offensive plays that took advantage of a particular defensive opponents weakness (a really effective one was called 10 Quick, 10 being our quarterback, where he would take the snap, count to one, and then spring up high, drilling a short pass right over the middle to the slanting end, usually coach’s son, Bob, who had great hands, and could catch in a crowd). We practiced all these things, and then proceeded into the season, with new T Square shoulder pads, and dazzling gold uniforms, beating all comers, only to lose to Patch in our only game with them that first season. But not by much. The season ended with a red hot need for revenge afire in our large young boy hearts. Next year could not come soon enough. But, we had to endure those gloating Patch pricks for the remainder of that school year.

1961 did come, with most of us being in the 9th, and 10th grades. If you started the season at age 15, you were good to go, but you had to pass the weigh in. The weight limit was raised that year, as we had all grown, so the games took on a more bruising character. That suited us just fine, although we had our share of broken bones, sprains, and contusions. Badges of honor all. We would wind up playing several games in horrible cold, wet, icy conditions in the early German winter, on fields that quickly turned to freezing mud. No Astroturf in those days.

We

won our first 4 games that second season by a margin of 184 points to

6. Our magnificent defense gave up almost no yardage, blocked punts,

forced turnovers, and kept our offense on the field for what seemed

like 80% of each game. We were high spirited, confident, and well

oiled. We would have eaten dirt for our coach, and burned with a

clear flame of barely contained explosive energy as we went into our

5th game against those undefeated devils from Patch. We beat them

22-0, and I got my shot at old Chuckie boy, putting him out of the

game with a safety blitz, you guessed it, head on tackle early in the

game. But, it was our defense once again that rose up, and gave us

good field position time after time, throwing Patch’s bigger

running backs for losses that forced punts that we blocked. Mike

Kolton was a huge, very fast Patch full back who 3 years later was

playing for Arizona State. On their first play from scrimmage, Kolton

was met head on (our practice really did pay off), for a loss in

their back field, by our crashing end, Bob Newman, and it never

slowed down from there. In what was a brutally physical game for 15

and 16 year olds, they never got their offensive rhythm, and never

figured out ours. They were out hit,

out

run, and off balance the whole game, but they were mostly out

coached. We were ready for that game.

The Black Knights of The Nekar won their next 4 games in mostly lop sided fashion, and had the league championship sewed up, because Bad Tolz, a team we had previously beat 30-6 that year, and who had been a hard 12-8 win for us in our second match up of the season, had managed an upset over Patch earlier.

Fickle fate dealt us a bad hand for the last game of the season against our old friends from Patch. A couple of our starters had rotated back to the US with their fathers before the season was over, our bruising full back was hurt, and our star quarterback was forced to miss the game due to serious illness. His back up had gone back to the good old USA, so we played with a quarterback who had not taken a snap all season. We lost that game. But, we were the champions, and they knew it.

On the way home, my dad told me what a great game I had played, what a great season we had had, and what a tremendous experience the whole two years had been. There was a lull in the conversation, and I simply said, “Dad, thanks for letting me play.” My father choked back a short bitter sob, an ever so quick one before his face composed itself again. He knew that I knew that he had just apologized. Nothing could have been less necessary.

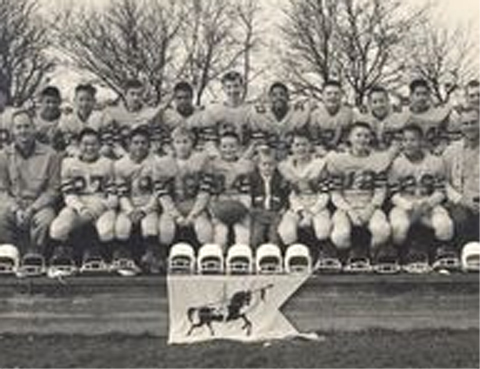

Pattonville Knights 1962; coach Stewart Newman on left |  Cheerleaders... |

Ever a teacher, he strove his entire life to say things to me that were deeply poignant, things that I would remember when he was gone. The one I am remembering now is what he told me after the championship banquet celebrating our Knight’s golden season, on the way home, when I told him that the high school football coach had stopped me in the hall at school, telling me that he hoped I would be around next year. My dad thought for a moment, and then said to me, “you are both fortunate, and not, that your first coach will probably be your best”. He was, of course, talking about Captain Newman, and I can hear his words clearly, still, like it was just yesterday. |  50 year reunion. |

I had a good high school football experience, and played a year of

college ball. My dad, gone now, was right with his prediction. I miss

him. But, I found my coach again.

Contact

Robert

(Unless you type

the

author's name

in the subject

line of the message

we won't know

where

to send it.)